(Bloomberg) — US public pension funds are on pace for their deepest financial setback since the Great Recession as turmoil in global markets this year threaten to leave taxpayers and government workers on the hook.

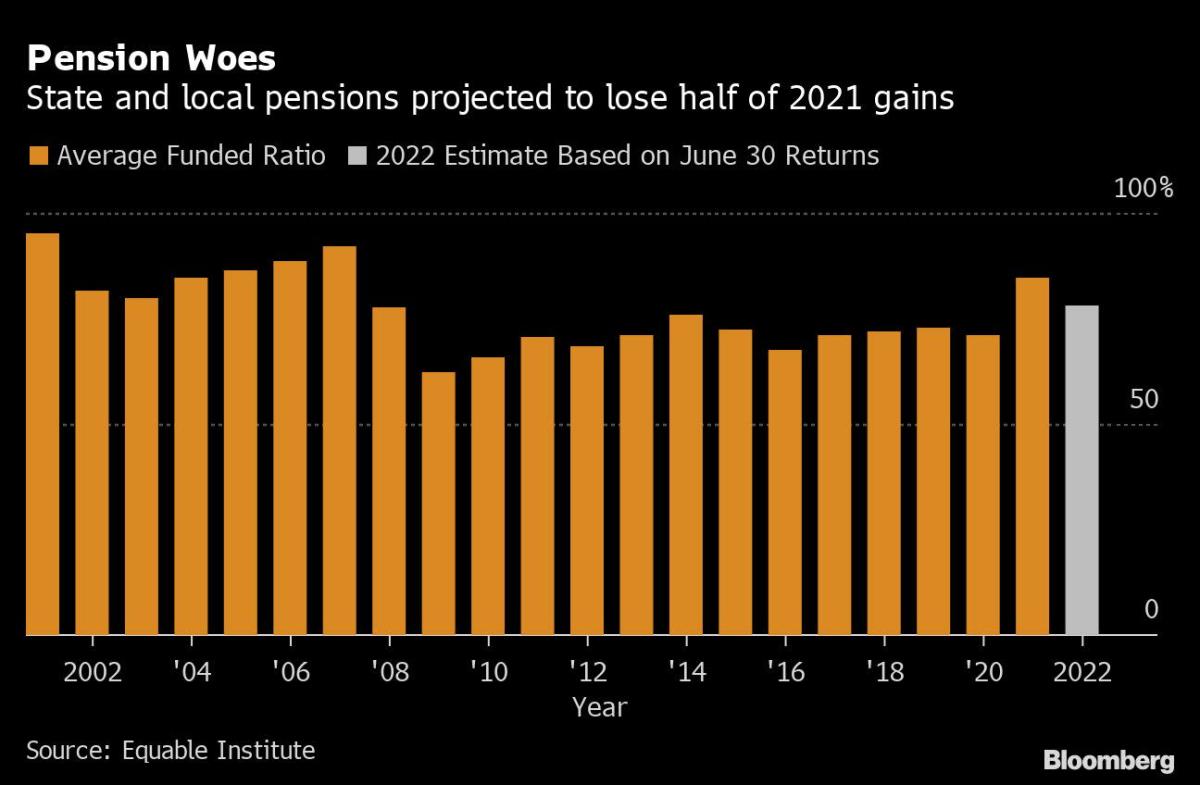

Steep stock and bond losses are set to leave state and local pensions this year with enough to cover 77.9% of all the benefits that have been promised, down from 84.8% in 2021, according to the New York-based nonprofit Equable Institute. That reflects almost a half trillion dollar increase in the gap between assets and what’s owed to retirees. The biggest US fund, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, said this week it lost 6.1%, its worst performance since 2009.

Public funds lost about 10.4% on average in 2022, according to Equable Institute, as surging inflation and growing fears of a recession hammered the bond market and drove stocks to their steepest quarterly decline since the first wave of Covid-19 in early 2020. The losses pared about half of the outsized 25% gain funds saw on average last year as monetary stimulus helped markets rally during the pandemic.

“The threat to states is not the investment losses,” said Equable executive director Anthony Randazzo. “The threat is the contribution rates that are going to have to go up because of the investment losses.”

When pensions miss their assumed annual return targets — about 7% on average — states and local governments have to increase funding or cut costs by raising employee contributions or freezing cost-of-living increases. To dampen the impact of market gyrations, most government pensions phase in additional contributions when returns fall short of targets.

Randazzo estimates that payroll contributions, currently around 30%, will climb to 35% in the next five to eight years.

The unfunded liability of public pensions had fallen to $933 billion in 2021 from $1.7 trillion a year earlier, according to Equable Institute. It’s projected to climb back to $1.4 trillion in 2022.

Wilshire Associates, a consultant to pension funds, earlier this month said losses in the second quarter left state retirement systems with assets sufficient to cover 70.1% of promised benefits, down from 81.4% the quarter prior.

Public pensions, which count on annual gains to cover benefits promised to retirees, have increased their allocations to riskier investments in stocks, private equity and high-yield bonds to meet long-term targets. A land war in Europe, inflation, tightening monetary policy and fear of recession of have led to widespread losses in some of those markets. Private equity now makes up more than 10% of state pension portfolios, according to Equable Institute.

The Public Employee Retirement System of Idaho lost 9.5% for the fiscal year ending June 30, the fourth-worst return in its history. The San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System — which was 112% funded in 2021 — fared comparatively well, losing a more modest 2.8%.

There is a silver lining, says Jean-Pierre Aubry, the associate director of state and local research at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. State and local governments have slowed liability growth by about half since 2000 by boosting contribution payments and narrowing benefits.

“This type of market of volatility results in higher contribution rates,” Aubry said. “But it doesn’t put the pension funds’ overall finances at real risk or the benefits being paid at any real risk.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.