(Bloomberg) — In times of Treasury turmoil, the biggest investor outside American soil has historically lent a helping hand. Not this time round.

Japanese institutional managers — known for their legendary U.S. debt buying sprees in recent decades — are now fueling the great bond selloff just as the Federal Reserve pares its $9 trillion balance sheet.

The latest data from BMO Capital Markets show the largest overseas holder of Treasuries has offloaded almost $60 billion over the past three months. While that may be small change relative to the Japan’s $1.3 trillion stockpile, the divestment threatens to grow.

That’s because the monetary path between the U.S. and the Asian nation is diverging ever more, the yen is plumbing 20-year lows and market volatility stateside is breaking out. All that is ramping up currency-hedging costs and completely offsetting the appeal of higher nominal U.S. yields, especially among large life insurers.

The upshot: Japanese accounts are contributing to the historic Treasury rout and may not return en masse until the benchmark 10-year yield trades firmly above 3%. In fact, near-zero-yielding bonds at home look ever-more appealing even as U.S. debt offers some of the highest rates in years.

“It’s a significant amount of selling and on par with what we saw in early 2017 from Japan,” said Ben Jeffery, BMO’s rates strategist.

While an aggressive Fed tightening cycle to combat inflation could result in multiple 50 basis-point hikes in the coming months, the Bank of Japan remains locked in endless stimulus. That’s weakening the yen and upending the economics of buying Treasuries even as the 10-year Japanese government bond remains capped around 0.25%.

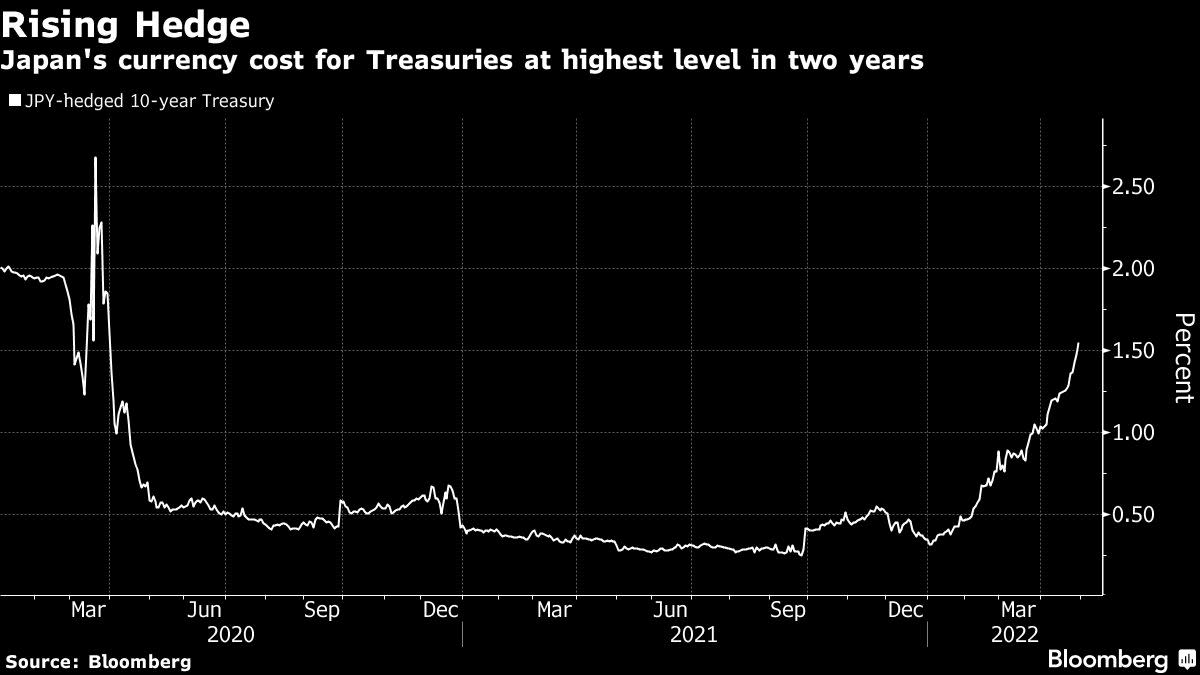

While the selloff has pushed the 10-year U.S. yield to around 2.9%, buyers who pay to protect against fluctuations in the yen-dollar exchange rate see their effective yields dwindle to just 1.3%. That’s because hedging costs have ballooned to 1.55 percentage points, a level not seen since early 2020 when the global demand for dollars spiked in the pandemic rout.

A year ago the Treasury security was offering a similar yield, when accounting for the cost of protecting against moves in the exchange rate thanks to a modest 32 basis-point hedging cost.

“Hedge costs are the issue for investing in U.S. Treasuries,” said Eiichiro Miura, general manager of the fixed-income department at Nissay Asset Management Corp.

Fed tightening cycles and the associated market volatility have tempered Japanese buying of Treasuries in the past. But in this cycle, the high level of uncertainty surrounding U.S. inflation and interest-rate policy may trigger an extended absence. At the same time, Japanese traders returning from the Golden Week holiday have other offshore options as euro-hedging costs remain near the one-year average.

“In the span of next six months or so, investing in Europe is better than the U.S. as hedge costs are likely to be low,” said Tatsuya Higuchi, executive chief fund manager at Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management Co. “Among the euro bonds, Spain, Italy or France look appealing given the spreads.”

Typically, Japanese buying has favored intermediate sectors of the Treasury curve from five- to 10-year notes, while life insurers and pension funds have focused on 30-year bonds. But hopes that the Treasury market would see long-end buying in the new financial year that began in April have been dashed as some big life insurers rethink their exposure to overseas debt, given currency volatility spurred in large part by the hawkish monetary shift at the U.S. central bank.

“The Fed is being super aggressive,” said John Madziyire, portfolio manager at Vanguard Group Inc. “Are you really going to buy when Treasuries will probably get to more attractive levels?”

One broad Treasury index is already sitting on a more than 8% loss so far this year. Much now rests on whether the 10-year can consolidate in a range of 2.80% to 3.10% this month once the upcoming Fed meeting is absorbed by the market along with quarterly debt sales from the U.S. Treasury.

“Japanese investors will wait for some stabilization in long-dated yields before they sense a buying opportunity,” said George Goncalves, head of macro strategy at MUFG. “If the 10-year settles during May, that will help attract buyers and at those yield levels you are getting compensated now.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.