(Bloomberg) — The price of copper — used in everything from computer chips and toasters to power systems and air conditioners — has fallen by nearly a third since March. Investors are selling on fears that a global recession will stunt demand for a metal that’s synonymous with growth and expansion.

You wouldn’t know it from looking at the market today, but some of the largest miners and metals traders are warning that in just a couple of years’ time, a massive shortfall will emerge for the world’s most critical metal — one that could itself hold back global growth, stoke inflation by raising manufacturing costs and throw global climate goals off course. The recent downturn and the under-investment that ensues only threatens to make it worse.

“We’ll look back at 2022 and think, ‘Oops,’” said John LaForge, head of real asset strategy at Wells Fargo. “The market is just reflecting the immediate concerns. But if you really thought about the future, you can see the world is clearly changing. It’s going to be electrified, and it’s going to need a lot of copper.”

Inventories tracked by trading exchanges are near historical lows. And the latest price volatility means that new mine output — already projected to start petering out in 2024 — could become even tighter in the near future. Just days ago, mining giant Newmont Corp. shelved plans for a $2 billion gold and copper project in Peru. Freeport-McMoRan Inc., the world’s biggest publicly traded copper supplier, has warned that prices are now “insufficient” to support new investments.

Commodities experts have been warning of a potential copper crunch for months, if not years. And the latest market downturn stands to exacerbate future supply problems — by offering a false sense of security, choking off cash flow and chilling investments. It takes at least 10 years to develop a new mine and get it running, which means that the decisions producers are making today will help determine supplies for at least a decade.

“Significant investment in copper does require a good price, or at least a good perceived longer-term copper price,” Rio Tinto Group Chief Executive Officer Jakob Stausholm said in an interview this week in New York.

Why Is Copper Important?

Copper is essential to modern life. There’s about 65 pounds (30 kilograms) in the average car, and more than 400 pounds go into a single-family home.

The metal, considered the benchmark for conducting electricity, is also key to a greener world. While much of the attention has been focused on lithium — a key component in today’s batteries — the energy transition will be powered by a variety of raw materials, including nickel, cobalt and steel. When it comes to copper, millions of feet of copper wiring will be crucial to strengthening the world’s power grids, and tons upon tons will be needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use more than twice as much copper as gasoline-powered cars, according to the Copper Alliance.

How Big Will the Shortage Get?

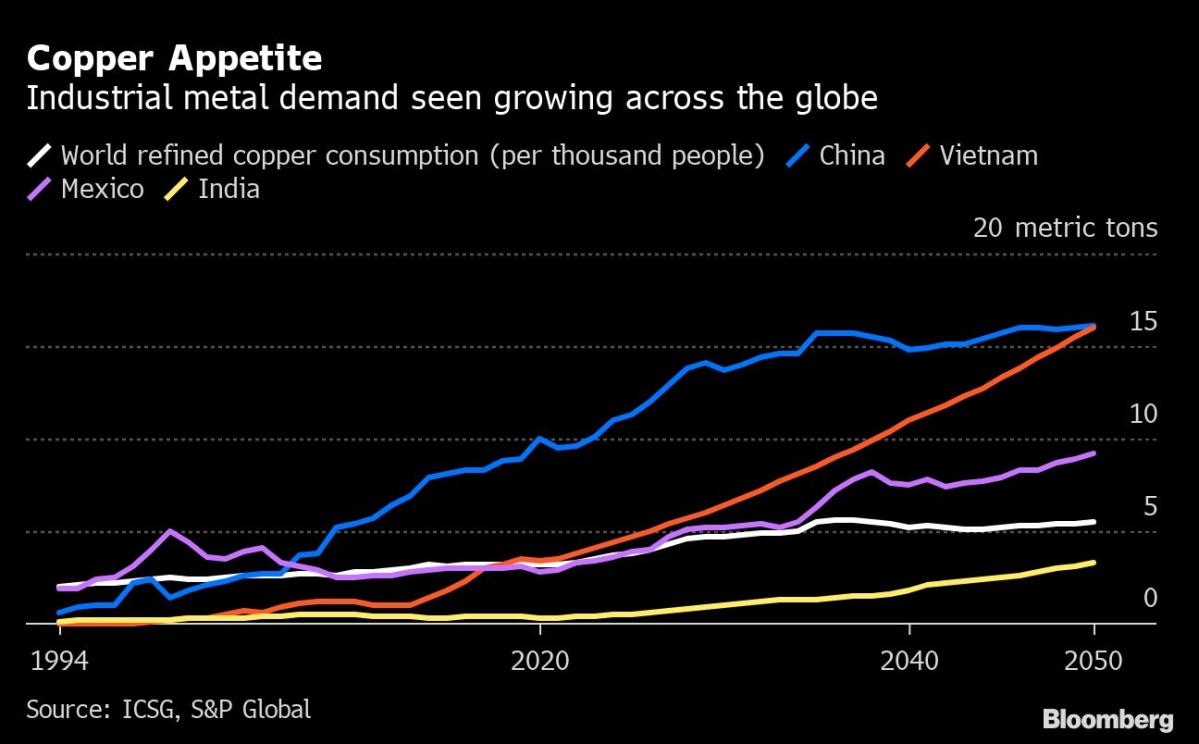

As the world goes electric, net-zero emission goals will double demand for the metal to 50 million metric tons annually by 2035, according to an industry-funded study from S&P Global. While that forecast is largely hypothetical given all that copper can’t be consumed if it isn’t available, other analyses also point to the potential for a surge. BloombergNEF estimates that demand will increase by more than 50% from 2022 to 2040.

Meanwhile, mine supply growth will peak by around 2024, with a dearth of new projects in the works and as existing sources dry up. That’s setting up a scenario where the world could see a historic deficit of as much as 10 million tons in 2035, according to the S&P Global research. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates that miners need to spend about $150 billion in the next decade to solve an 8 million-ton deficit, according to a report published this month. BloombergNEF predicts that by 2040 the mined-output gap could reach 14 million tons, which would have to be filled by recycling metal.

To put in perspective just how massive that shortage would be, consider that in 2021 the global deficit came in at 441,000 tons, equivalent to less than 2% of demand for the refined metal, according to the International Copper Study Group. That was enough to send prices jumping about 25% that year. Current worst-case projections from S&P Global show that 2035’s shortfall will be equivalent to about 20% of consumption.

As for what that means for prices?

“It’s going to get extreme,” said Mike Jones, who has spent more than three decades in the metal industry and is now the CEO of Los Andes Copper, a mining exploration and development company.

Where Are Prices Heading?

Goldman Sachs forecasts that the benchmark London Metal Exchange price will almost double to an annual average of $15,000 a ton in 2025. On Wednesday, copper settled at $7,690 a ton on the LME.

“All the signs on supply are pointing to a fairly rocky road if producers don’t start building mines,” said Piotr Kulas, a senior base metals analysts at CRU Group, a research firm.

Of course, all those mega-demand forecasts are predicated on the idea that governments will keep pushing forward with the net-zero targets desperately needed to combat climate change. But the political landscape could change, and that would mean a very different scenario for metals use (and the planet).

And there’s also a common adage in commodity markets that could come into play: high prices are the cure for high prices. While copper has dropped from the March record, it’s still trading about 15% above its 10-year average. If prices keep climbing, that will eventually push clean-energy industries to engineer ways to reduce metals consumption or even seek alternatives, according to Ken Hoffman, the co-head of the EV battery materials research group at McKinsey & Co.

Scrap supply can help fill mine-production gaps, especially as prices rise, which will “drive more recycled metals to appear in the market,” said Sung Choi, an analyst at BloombergNEF. S&P Global points to the fact that as more copper is used in the energy transition, that will also open more “opportunities for recycling,” such as when EVs are scrapped. Recycled production will come to represent about 22% of the total refined copper market by 2035, up from about 16% in 2021, S&P Global estimates.

The current global economic malaise also underscores why the chief economist for BHP Group, the world’s biggest miner, just this month said copper has a “bumpy” path ahead because of demand concerns. Citigroup Inc. sees copper falling in the coming months on a recession, particularly driven by Europe. The bank has a forecast for $6,600 in the first quarter of 2023.

And the outlook for demand from China, the world’s biggest metals consumer, will also be a key driver.

If China’s property sector shrinks significantly, “that’s structurally less copper demand,” said Timna Tanners, an analyst at Wolfe Research. “To me, that’s just an important offset” to the consumption forecasts based on net-zero goals, she said.

But even a recession will only mean a “delay” for demand, and it won’t “significantly dent” the consumption projections going into 2040, according to a presentation from BloombergNEF dated Aug. 31. That’s because so much of future demand is being “legislated in,” through governments’ focus on green goals, which makes copper less dependent on the broader global economy than it used to be, said LaForge of Wells Fargo.

Plus, there’s little wiggle room on the supply side of the equation. The physical copper market is already so tight that despite the slump in futures prices, the premiums paid for immediately delivery of the metal have been moving higher.

What’s Holding Back Supplies?

Just take a look at what’s happening in Chile, the legendary mining nation that’s long been the world’s largest supplier of the metal. Revenue from copper exports is falling because of production struggles.

At mature mines, the quality of ore is deteriorating, meaning output either slips or more rock has to be processed to produce the same amount. And meanwhile the industry’s pipeline of committed projects is running dry. New deposits are getting trickier and pricier to both find and develop. In Peru and Chile, which together account for more than a third of global output, some mining investments have stalled, partly amid regulatory uncertainty as politicians seek a greater portion of profits to resolve economic inequalities.

Soaring inflation is also driving up the cost of production. That means the average incentive price, or the value needed to make mining attractive, is now roughly 30% higher than it was 2018 at about $9,000 a ton, according to Goldman Sachs.

Globally, supplies are already so tight that producers are trying to squeeze tiny nuggets out of junky waste rocks. In the US, companies are running into permitting roadblocks. While in the Congo, weak infrastructure is limiting growth potential for major deposits.

Read More: Biggest US Copper Mine Stalled Over Sacred Ground Dispute

And then there’s this great contradiction when it comes to copper: The metal is essential to a greener world, but digging it out of the earth can be a pretty dirty process. At a time when everyone from local communities to global supply chain managers are heightening their scrutiny of environmental and social issues, getting approvals for new projects is getting much harder.

The cyclical nature of commodity industries also means producers are facing pressure to keep their balance sheet strong and reward investors rather than aggressively embark on growth.

“The incentive to use cash flows for capital returns rather than for investment in new mines is a key factor leading to a shortage of the raw materials that the world needs to decarbonize,” analysts at Jefferies Group LLC said in a report this month.

Even if producers switch gears and suddenly start pouring money into new projects, the long lead time for mines means that the supply outlook is pretty much locked in for the next decade.

“The short-term situation is contributing to the stronger outlook longer term because it’s having an impact on supply development,” Richard Adkerson, CEO of Freeport-McMoRan, said in an interview. And in the meantime, “the world is becoming more electrified everywhere you look,” he said, which inevitably brings “a new era of demand.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.