History says that another big drop is coming soon. Here’s what investors need to know now.

If you think stocks have already hit their bottom, Howard Marks might convince you otherwise.

Since March 23, the S&P 500 has rallied nearly 25%, beginning a brand new bull market within just weeks of the previous one’s end.

But according to data compiled by Marks, the co-founder of Oaktree Capital, in the last two bear markets, the first big comeback rallies have historically been followed by sharp declines until a bottom is eventually reached.

“The first and second declines were followed by substantial rallies… which then gave way to even bigger declines,” Marks wrote in a memo this week.

Marks cited data from Gavekal Research’s Monthly Strategy note for April which posed the question of whether the market did in fact bottom on March 23. According to the Gavekal report, “markets early clear after one massive decline. In 15 bear markets since 1950, only one did not see the initial major low tested within three months… In all other cases, the bottom has been tested once or twice. Since news-flow in this crisis will likely worsen before it improves, a repeat seems likely.”

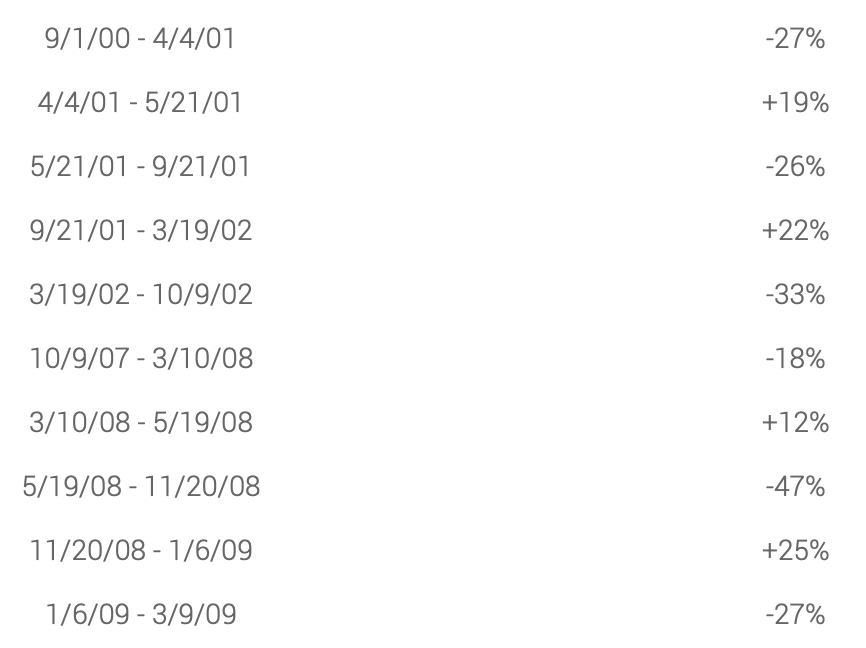

Marks outlined that between September 2000 and April 2001, the S&P 500 dropped 27% as the dotcom bubble burst. After that, the index rallied 19% between April 2001 and May 21 of that year. Those gains were then wiped out by a 26% pullback through September 2001, followed by the index rising 22% through late March 2002 only to drop 33% and ultimately reach a bottom in October 2002.

There was a similar pattern between late 2007 and early 2009 amid the financial crisis, with the S&p 500 dropped 18% between October 9, 2007 and March 10, 2008. That decline was followed by a gain of 12% through late May 2008, before the index dropped 47% through November 2008. That was followed up by a 25% rally through early January 2009, before the index dropped another 27% to finally reach a bottom in March 2009.

So far amid the coronavirus crisis, the S&P 500 fell nearly 34% between its record high reached on February 19 and March 23 – the date many are saying was the bottom of the bear market.

The market’s wild moves since then have come as the coronavirus pandemic has roiled economic activity and growth expectations alongside dwindling consumer sentiment.

“The bottom line for me is that I’m not at all troubled saying markets may well be considerably lower sometime in the coming months,” Marks wrote in the memo.

Marks isn’t the only one who sees more downside ahead.

Goldman Sachs’ chief equity strategist David Kostin said this week that the recent optimism in the stock market doesn’t necessarily constitute an “all-clear” signal for bullish investors seeking a path higher.

“There’s a little bit of asymmetry in terms of the downside risk toward a level in the S&P 500 of around 2,000, which is down almost 25%, and upside of around 10% to a target at the end of the year of 3,000,” Kostin said.

While that’s a wide range of possible outcomes, it speaks to the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic-stricken economy and the markets once we’re in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak. There are glimmers of hope that the virus curve is flattening, however, the economic cracks are becoming evermore apparent. One need only look at the unemployment rate, which is now around 15%, for a hint as to the economic damage done due to the nationwide shutdowns to slow the spread of the virus.

Even still, Marks is taking the opportunity to add to his equity exposure.

“The risks in the environment are recognized and largely understood,” Marks wrote. “Thus, I feel it’s a time when previously cautious investors can reduce their overemphasis on defense and begin to move toward a more neutral position or even toward offense.”

“So, It’s my view that waiting for the bottom is folly,” Marks said. “What, then, should be the investor’s criteria? The answer is simple: if something is cheap—based on the relationship between price and intrinsic value—you should buy, and if it cheapens further, you should buy more.”