(Bloomberg) — Treasury investors are losing more money than they have in four decades, once inflation is taken into account. And if markets are right, they’re unlikely to come out ahead for years.

The federal government’s debt has already lost about 2% outright over the past year as the Federal Reserve started removing pandemic-era stimulus from the economy and inched closer toward raising interest rates. But on top of that, the consumer price index has surged 6.8%, putting investors even deeper in the hole.

Taken together, that’s resulting in the worst real returns — or those adjusted for inflation — since the early 1980s, when then Fed Chair Paul Volcker was in the midst of fighting a wage-price spiral. What’s more, the dynamic isn’t expected to change: The bond market is projecting that 10-year Treasury yields will hold below the inflation rate for the next decade, meaning any investment income will be more than wiped out by the rising cost of living.

The persistently low level of long-term yields in the face of the steepest inflation in decades has been a major puzzle on Wall Street, since it defies the textbook expectation that investors would demand higher payouts in return. In 1982, last time year-on-year inflation surged as much as it did in November, the 10-year yield climbed as high as nearly 15%. It’s below 1.5% now.

Some say that reflects the deluge of stimulus and rising household savings since the onset of the pandemic, which has left a surfeit of cash flooding into the Treasury market. For others, it reflects a pessimistic view of the economy, signaling that investors see the nation’s growth potential continuing to slip under an aging population.

Either way, nearly two years of sub-zero real yields have penalized average savers and bond investors to the benefit of the federal government.

“People have accepted negative real returns for a long period of time,” said Greg Whiteley, portfolio manager at DoubleLine Group, which oversees $137 billion in assets. “Despite the fact it may seem peculiar, maybe this is something we have to adjust to as the new normal. The long-term secular drivers are still in place, and they are still going to be powerful.”

Ten-year yields on inflation-linked bonds fell to an all-time low of minus 1.25% last month before rebounding to about minus 1%. Taken at face value, that shows investors expect 10-year yields –trading at 1.44% Monday — to trail inflation by about 1% annually over the next decade.

“You many not want to own bonds because they are negative-yielding security,” said Francis Scotland, director for global macro research at Brandywine Global, which manages $67 billion in assets. “But that phenomenon may exist for a long time because of this fundamental disequilibrium between saving and investment, or spending and saving.”

Even so, there are some temporary factors at work. While the Fed has started paring its bond purchases, it’s still buying $60 billion worth of Treasuries a month. All told, the central bank has absorbed more than $3 trillion of Treasuries since February 2020, taking the pressure off public buyers. Meanwhile, many pension funds are almost fully funded for the first time since 2008, thanks to the stock rally, giving them incentives to buy fixed-income to reduce the risk exposure in their portfolio.

That supply-demand imbalances may change next year as central banks worldwide retreat from their quantitative easing, which would lead to higher bond yields, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. The global demand for bonds is likely to drop by $3.1 trillion next year, more than the expected $2.3 trillion decline in net supply, according to JPMorgan’s strategist Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou.

But any increase in yields will likely be moderate. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. strategists led by Praveen Korapaty predict that 10-year real yields will only rise to minus 0.85% next year, leaving them in a negative territory for a record third year in a row.

What’s underpinned the negative yields is the fact that investors have persistently priced in one of the least aggressive rate-hiking campaigns in history.

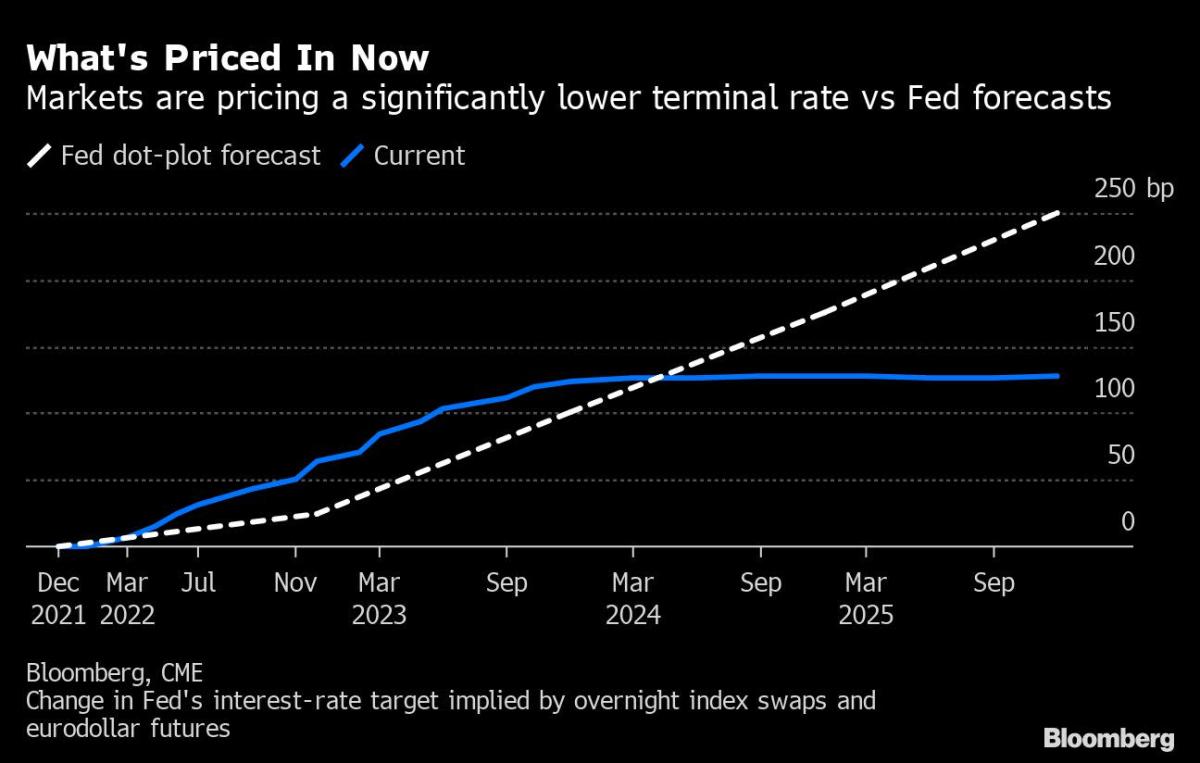

Markets are currently predicting just five 25 basis-point rate increases that would end with the Fed’s benchmark at about 1.5% by the end of 2024. By comparison, the central bank lifted rates by a total of 2.25 percentage points and 4.25 percentage points in the last two tightening cycles.

The Fed’s own dot-plot forecast in September anticipates that rates will rise to 1.75% by 2024 and that it won’t reach a neutral level until 2.5%. Fed officials may hit an even higher rate projection when they release fresh forecasts for the economy and the dot-plot at the policy meeting Wednesday.

Margie Patel, senior portfolio manager at Allspring Global Investments, doubts that the Fed will raise rates all the way to the neutral level.

“There’s not impetus for the Fed to slam on the breaks — and they know when they do so they cause recessions,” said Patel, whose firm manages $587 billion in assets. “They have repressed interest rates, they are going to keep repressing interest rates.”

The combination of low yields and high inflation this year has taken a toll on bond buyers, forcing them to look elsewhere for higher returns. Over the past decade, Bloomberg’s U.S. Treasury index gained 2.3% a year, barely beating consumer price increases even during periods of relatively tame inflation. Meanwhile, even as the government debt swelled since the pandemic, its interest expense declined to 2.5% of the gross domestic product in the fiscal year ended in September from 2.7% in 2019.

“We haven’t been excited about negative real rates,” said Christian Hoffmann, portfolio manager at Thornburg Investment Management. “This has become less of a free market. We are not taking a lot duration risks at all.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.