Social Security had another disastrous financial year in 2022 even as it hurtles toward insolvency.

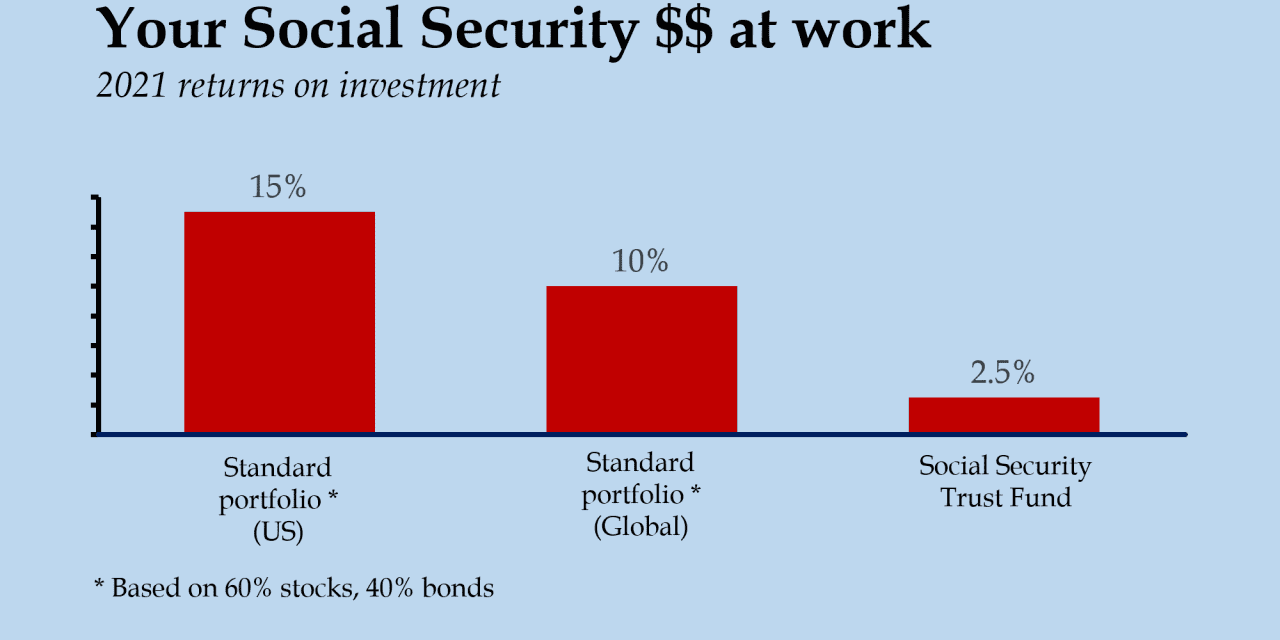

America’s main pension plan saw its investments badly trail the booming markets, competitors, and even inflation, yet again thanks to a rigid investment policy that hasn’t been changed since 1935. The trust fund earned just 2.5% on every dollar invested last year, the trustees have just revealed. That compared with a stellar year on financial markets, where the S&P 500 shot up 29%, international stocks 11%, real estate trusts 32% and commodities 26%.

Nearly all U.S. workers are compelled by law to pay 12.4% of every dollar they earn into the Social Security trust fund, yet last year their money earned just a quarter of the returns of a typical global pension plan, and just one-sixth of what they would have earned in a basic Vanguard Balanced Index Fund.

The fund’s returns were also less than half the rate of inflation, meaning that in real, purchasing power terms workers lost 4% of their money.

Social Security’s investments have underperformed basic pension fund benchmarks in 4 of the last 5 years, 8 of the last 10, 11 of the past 13, and in two-thirds of all years since 1980. The average underperformance during the past 4 decades has been about 4.5% a year.

The plan is required to invest 100% of its money in U.S. Treasury bonds, under the terms of the 1935 law that created it. Almost no other pension plan in the world operates like that. The rest invest mostly in more profitable stocks, real estate and other assets. The typical U.S. pension plan, other than Social Security, keeps about 80% of its money in stocks and alternative investments such as commodities, real estate and hedge funds, and less than a quarter in bonds of any kind — including not only safe Treasurys but also things like corporate bonds, which are riskier but earn higher returns.

The unique Treasurys-only policy was set by the Social Security Act of 1935. At the time stocks were out of fashion: The U.S. was still reeling from the aftershocks of the great Wall Street crash of 1929-1932, when U.S. stocks fell about 90%.

President Franklin Roosevelt had another reason to keep the new program’s money in U.S. government bonds: It provided easy money to help pay for the New Deal. But the policy has proven disastrously costly to the trust fund and the workers who rely on it. Since the mid-1930s, U.S. stocks have outperformed Treasury bonds in total by more than 6,000%. The average big U.S. pension plan, other than Social Security, is today expecting to earn an average return of about 7% a year. Last month Social Security was investing all new FICA taxes in bonds paying 1.5% interest.

Social Security’s disastrous investment returns come as the fund braces for crisis and possible insolvency. In 2022 the trustees reported that the hole in the fund’s accounts had grown by $3 trillion in the previous 12 months, the biggest annual rise on record. Social Security is now underfunded to the level of $20 trillion, or nearly 100% of U.S. gross domestic product. Unless drastic action is taken, benefits will have to be cut by about a fifth across the board starting in a decade.

Such drastic action is expected to include tax hikes and benefit cuts. The last time this happened, in the 1980s, the government responded by walloping Social Security beneficiaries with benefits taxes for the first time.

If the trust fund had been invested in a regular mixture of stocks and bonds throughout its history, like every other pension plan, there would be no funding crisis. About 65 million Americans currently receive Social Security benefits. Most are retired workers, though they also include widows, orphans and those with disabilities. Another 175 million Americans currently pay into the system.

Despite the looming crisis in Social Security, many of its underlying principles are currently subject to little political debate. There is, for example, little or no political pressure to change its made-in-1935 investment strategy, even though it has been provably disastrous and no other comparable pension plan pursues such a strategy. Equally, there seems little demand to end the system whereby Social Security is financed by a flat, even regressive, 12.4% income tax—even among people who otherwise consider all flat taxes obnoxious. (The tax caps out on incomes above about $143,000.)

The result is that someone on minimum wage must hand over $1 out of every $8 that they make to an investment operation that is designed by law to lose them money. And nobody says peep—not even those who complain frequently about how hard it is to keep body and soul together on the minimum wage.

If Social Security hits insolvency, both liberals and conservatives in politics can be expected to try to turn the crisis to their advantage. As someone once said, you never want to let a crisis go to waste. Meanwhile few of those in the political class will be affected personally when the crisis arrives. For those connected to the Beltway economy, their wealth, federal salaries, outside incomes, and matchless contacts mean that a future Social Security cut, even of 20% or more, will barely register.