(Bloomberg) — On the surface, the recent land auction by the Chinese city of Rizhao appeared routine. There were four bids, pushing the price up 11% to $170 million. A closer look reveals something curious: The offers were reportedly made by a finance entity owned by the Rizhao government, meaning the city effectively sold land to itself.

Across China, local government financing vehicles have replaced cash-strapped property developers as the biggest buyers of land for real estate development, stoking fresh concerns over the ability of these off-balance sheet borrowers to repay a debt pile that tops $8.4 trillion by some estimates.

In nine of 21 large Chinese cities that packed in land sales over the last two months of 2021, at least half of the plots were bought by these so-called LGFVs, according to consulting firm China Index Holdings. Some of these purchases were worth billions of dollars.

While the moves may help arrest a land sale slump and provide much-needed revenue for local governments, the purchases threaten to exacerbate risks for LGFVs — the second-biggest non-financial borrowers in the offshore market and the biggest onshore.

“Purchasing land will usually lead LGFVs to pile up borrowings and increase leverage,” said Yuqing Fu, a portfolio manager of the HSBC Jintrust Stable Income Bond Fund. “It’s not easy for them to pare them down afterwards.”

Rizhao’s LGFV declined to comment on the multiple bids at the auction last month, which was reported by The Paper. Calls to the city’s land authority went unanswered.

LGFVs rose to prominence in the wake of the financial crisis, when city and provincial governments were cut off from borrowing. The vehicles filled the void, tapping debt markets and bank loans to finance roads, bridges and subways across China. Their liabilities exploded, though compiling a precise tally is hard since much of the debt is kept off city balance sheets. Even before the recent land buying binge, the International Monetary Fund estimated LGFV debt was about 39 trillion yuan ($6.2 trillion) in 2020. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. puts it at 53 trillion yuan, or about half of China’s gross domestic product.

LGFVs have been a looming risk in China’s credit market for years, yet the implicit guarantees from local governments have helped avoid defaults on public bonds, ensuring steady investor demand. Though Beijing has outlawed explicit guarantees, the expectation that a city or provincial government would ultimately support a struggling LGFV has prompted ratings companies to give some of them the equivalent of investment-grade ratings.

Even amid the recent bond meltdown sparked by defaults at China Evergrande Group and other developers, the LGFV debt has held up well. A gauge of offshore bonds sold by LGFVs are hovering near a December record high, according to an iBoxx index.

Still, risks are rising on a few fronts. The vehicles are scooping up land just as prices are falling and the property market craters. Proceeds from land sales have dropped for four straight months, dealing a blow to local governments that count on these sales for as much as 40% of revenue. If developers continue to scale back on construction, the LGFVs could be stuck with vacant lots.

While the multiple bidding that took place in Rizhao doesn’t appear to be widespread, it’s clear the finance vehicles are ramping up spending. The LGFVs bought roughly 30% of all parcels sold nationwide in recent months, and almost 50% in smaller counties, according to Yan Yuejin, research director at E-house China Research and Development Institute.

Examples include Shenzhen Metro Group Co., the biggest LGFV issuer in Guangdong province, which spent 18 billion yuan for five of the 11 plots on auction in November. Its land spending last year exceeded total revenue for 2020. Similarly, the property unit of AA+ rated LGFV Jiangsu Wuzhong Economic Technology Development Group Co. bid on two parcels in eastern Suzhou worth 5.4 billion yuan.

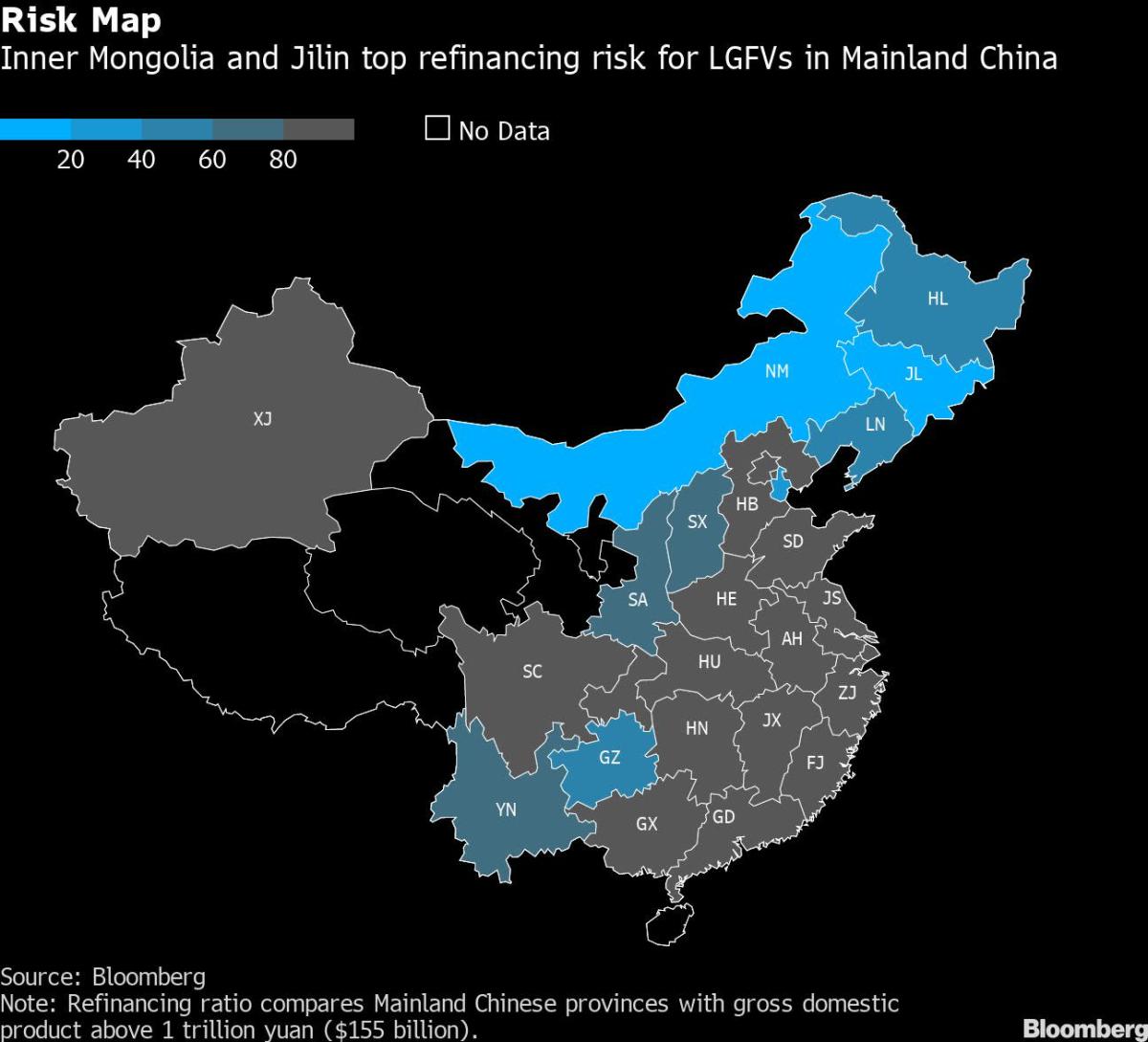

The LGFVs meanwhile face refinancing risks as Beijing looks to clamp down on debt that’s not on government balance sheets. As part of this push, the central government wants to break the implicit state guarantees backing these opaque liabilities, potentially putting LGFV investors at risk down the road. The entities face a maturity wall of $376 billion this year, with the majority onshore, according to Bloomberg-compiled data.

Financial institutions, which have 25 trillion yuan in LGFV exposure — or 37% of total loans — are also turning cautious. At least five state-run banks have imposed new restrictions this year on loans to weaker LGFVs, Bloomberg reported this month.

LGFVs in areas with slumping land sales, including Yunnan, Jiangxi, Inner Mongolia and Guangxi, face higher repayment risks, S&P Global Ratings said in a report dated Monday.

Weaker land sales and the ongoing campaign to curb hidden debt may push a few of the weaker LGFVs into distress this year, said Freddy Wong, head of Asia-Pacific fixed income at Invesco Ltd., who expects the default rate to remain very low for the sector overall.

These moves “will leave less leeway to local governments in weak regions” to support their LGFVs, he said.

For the stronger entities, the risks may be further out. Governments will likely maintain support this year, as their own fiscal challenges make them more reliant on LGFVs for infrastructure investments, said Zerlina Zeng, senior analyst at CreditSights Singapore LLC. Regional authorities also want to avoid disorderly defaults with a five-year shuffle of leadership coming up this year.

“We may not see obvious risks in the short-term,” said Feng Jianlin, chief analyst of research institute FOST in Beijing. “But if LGFVs continue to be the main land buyers, the risks should be taken seriously.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.