(Bloomberg) — To many on Wall Street, the painful selloff that’s been racing through the Treasury market this month is only the opening act.

On Wednesday, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s hawkish tone added fuel to the rout after he said the bank is poised to start raising interest rates in March, sending two-year Treasury yields surging the most since March 2020. Money markets swiftly started pricing in nearly five Fed hikes this year, up from three expected as recently as December.

But a chorus of bond analysts and investors say the markets are still underestimating how far the Fed will need to go to tame an inflation surge that’s more persistent and steeper than policymakers once expected.

The upshot, if the bears are right: bond yields will need to jump a lot more — and stay there — to get borrowing costs anywhere near high enough to prevent the economy from overheating, threatening a deeper hit for bondholders already seeing their worst monthly losses since late 2016.

“They are behind the curve and they are guilty of being too easy for too long,” David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, said of the Fed.

The central bank is treading a delicate path as it pulls back the massive stimulus measures that have helped economic growth surge amid the pandemic. Facing the biggest jump in inflation in four decades, it needs to raise rates enough to bring consumer prices under control without setting off a recession.

Despite the sharp rise in Treasury yields this month, those rates — which serve as a benchmark for the financial system — remain historically low, with yields still below the expected rate of inflation. That suggests confidence that growth and inflation will slow later this year and eventually enable the Fed to raise its overnight rate only a little above 2% during the current business cycle. It’s currently near zero.

“The market doesn’t believe the economy can survive 6-7 hikes in the next 18 months,” said Aneta Markowska, chief U.S. financial economist at Jefferies, who thinks traders are off-base with that view.

On Wednesday, Powell acknowledged that growth is stronger and inflation higher than when the Fed previously kicked off hiking cycles, signaling the possibility of a more rapid pace of monetary-policy tightening beginning in March. He expressed confidence that the economy can handle higher interest rates, while also leaving the door open to a 50-basis-point shift higher, a tightening step not seen since 2000.

His remarks ignited a bond selloff that by Thursday morning in New York had driven the policy-sensitive two-year note’s yield to 1.20%, up 20 basis points from before the Federal Open Market Committee meeting and Powell’s press conference.

Money-market traders boosted rate-hike bets to price in about 117 basis points of increases in 2022 — or almost five quarter-point moves — up from about 100 basis points before the meeting.

“Powell was much more hawkish than expected,” said George Goncalves, head of U.S. macro strategy at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. “The Fed is clearly behind the curve and is using every opportunity to get back on sides. We still believe this ultimately will result in a policy error in the other direction. But for now they mean business in fighting inflation.”

A number of prominent observers — including former New York Fed President William Dudley, ex-Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and longtime money manager Mohamed El-Erian — have been warning for some time that the central bank has been too slow in clawing back its stimulus after its bond buying more than doubled the assets on its balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion since early 2020.

The Fed’s key interest rate remains near zero and it’s set to continue buying bonds until March, further stoking an economy marked by a tightening jobs market, rising wages and 7% annual inflation. The inflation adjusted, or real, 10-year Treasury yield is at minus 0.55%, a sign of ultra loose financial conditions. And the Fed’s expected path this year would leave the main overnight fed funds range around 1.25% by the end of the 2022, well below the rate of inflation and the approximately 4% rate economists see as no longer stimulative to growth.

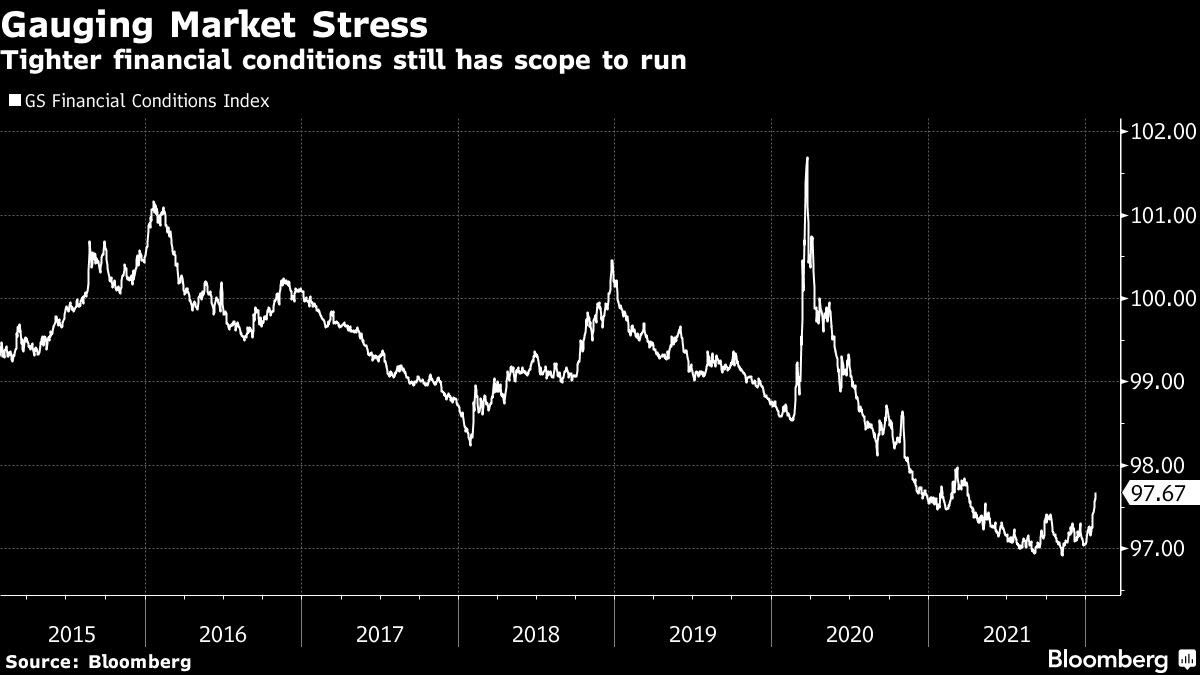

Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s financial conditions index is just above all-time lows, signaling that credit is still loose.

Stephen Roach, a former Morgan Stanley economist who now teaches at Yale University, said in an note this week that “the Fed is so far behind that it can’t even see the curve.”

“The Fed is pouring the fuel on an economy with the lowest unemployment rate in 40 years at a time when the inflation rate is probably more than double what it was in earlier periods of excessive monetary accommodation,” he said in an interview. “The Fed is going to have to do a heck of a lot more tightening.”

Some of that will come as the Fed starts shrinking its balance sheet by not buying new bonds when old ones mature, which it indicated it will start doing once rate hikes are under way. The bond market is alert to the prospect that such so-called quantitative tightening could intensify if the Fed is struggling to control inflation by raising rates.

Markowska, the economist at Jefferies, said the “structural tightness” in the labor market is something that hasn’t been seen since the 1950s and there’s “lots of cash sitting on corporate balance sheets and personal balance sheets, just waiting to be spent.”

“This inflation problem is not going to go away on its own,” she said. “The Fed is going to ultimately have to do something about it and I don’t think 7 hikes are going to do it. It’s going to take a lot more than what the market has already priced to get back to 2% inflation on a sustained basis.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.