(Bloomberg) — With famed open-outcry trading pits long since closed in Chicago and Kansas City, most of the shouting during wheat’s great blowup of 2022 came on social media or in the private confines of a home office.

James Neville, who’s been trading wheat and corn for 38 years, now prefers working from home in Fairway, Kansas, in front of five computer screens, where there’s no risk of getting spit on or stabbed with a pen, a not-uncommon occurrence on the trading floors of yore. He says he never seen a market moving faster than this one.

Wheat prices soared as much as 54% to a record of $13.635 a bushel in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The conflict led to a halt in shipments of wheat in the Black Sea hub where the two countries account for over a quarter of global exports. The war has also killed thousands and raised the risk of hunger for Ukrainians. Citizens in Africa and the Middle East dependent on grain from the Black Sea are also facing skyrocketing prices and a lack of food.

The World’s Next Food Emergency Is Here as War Compounds Hunger

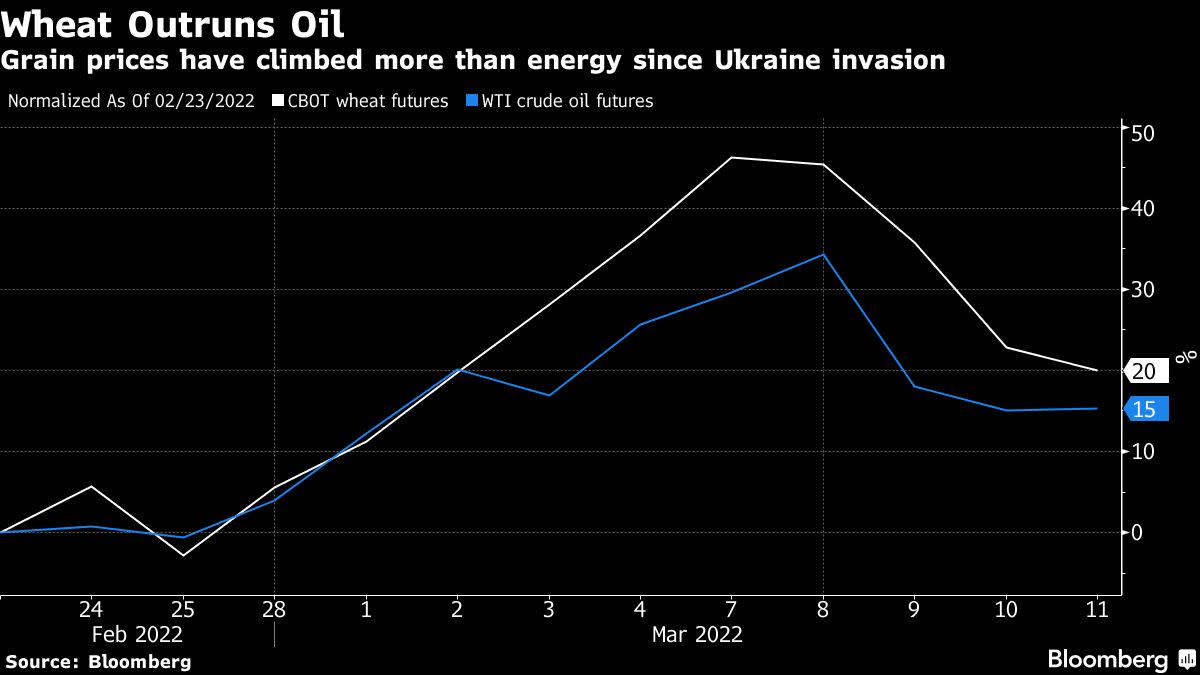

Extreme volatility in crop markets is exacerbating the situation. Surging futures had farmers eager to sell, while buyers at flour mills and bakeries have so far been balking at the higher costs. Gains in wheat have outstripped those in the crude oil market, although they trailed the moves in nickel.

“There is so much money pouring into these commodities markets now that it’s overwhelming the contracts,” Neville said by phone. “We don’t have a shortage of wheat in this country. We have a shortage of futures contracts,” he added, explaining that with everyone loading up on one side of the market, people can get trapped.

“I’ve seen this happen before. This one was just worse.”

Neville, who witnessed people throwing up in the bathroom during 1987’s Black Monday market crash, said he now makes sure to take his goldendoodle for a walk when things get too stressful. Still, he remains glued to his phone most days.

Wheat prices have cooled a bit after hitting a record March 8, and were headed for a weekly loss of 8%. However, without a resolution to the war, spring plantings for farmers in Ukraine are in doubt, which could drastically reduce the world’s supplies of wheat, corn and sunflower.

For commodity traders, that means monitoring markets nearly around the clock.

“Being around my computer at 7 o’ clock Sunday night is absolutely necessary,” said Ryan Ettner, a commodity broker at Allendale Inc. in Illinois. “Markets are so volatile, people just want that information right now.”

Ettner worked at Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., one of the world’s biggest crop traders, in 2008 when wheat had a similar move during the global financial crisis. Trading floors made it easy to see when big players were buying or selling. Now, he’s just getting a lot of late-night phone calls.

Even though rallies today lack the “rush of noise” you used to get from the trading pit, Ettner said. “This is the craziest time to be a trader since then.”

Lane Broadbent, president of commodity futures brokerage firm KIS Futures in Oklahoma City, said he had one client who missed out on the wheat rally in 2008 and now he’s determined to stay in the current market.

When overnight shelling sparked a fire at Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant last week, Broadbent fielded as many as 35 calls from panicked traders. He had been at a local basketball game at the time and stepped outside to put in trades.

Stressed-out clients told him, “I can’t sleep. I can’t concentrate. All I can think about are my futures markets.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.