(Bloomberg) — When Jim O’Neill devised the BRIC acronym at the turn of the century, the former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. chief economist did not intend the catchy phrase to be exploited for marketing investment funds.

Money managers scrambled to start funds anyway. The likes of Schroders Plc and Franklin Templeton — along with Goldman Sachs Asset Management — gobbled up billions of dollars from clients looking to profit by combining investments in Brazil, Russia, India and China. That marketing ploy has come crashing down and now faces an existential crisis.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made the former uninvestable, with MSCI Inc. removing it from benchmarks including the BRIC Index. China, which represents a major slice of this benchmark, is also slowing and has embarked on an unprecedented crackdown on technology companies that has led to sharp losses.

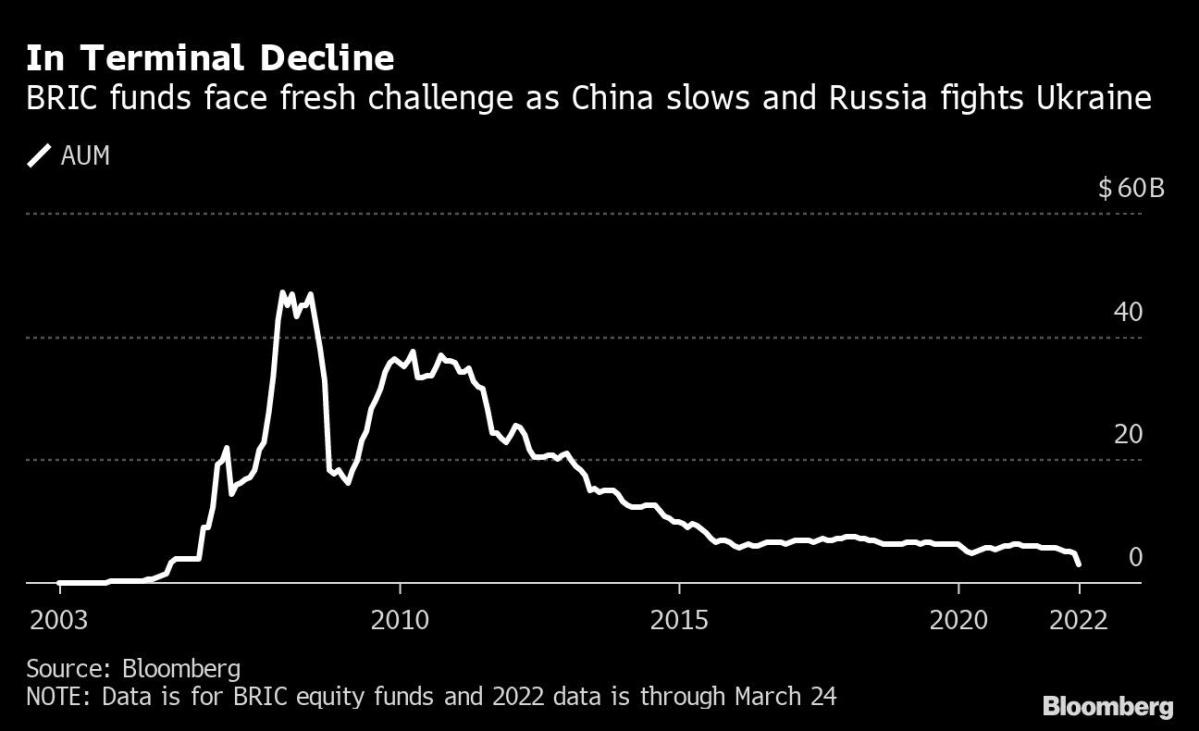

BRIC funds have lost 14.6% this year, while their combined assets have slumped by more than 90% from their peak to about $3 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The collapse holds a ruthless lesson for investors on the perils of thematic funds. Combining four diverse, complex and risky emerging market countries in a fund was clever wordplay but not a smart bet. While the economies grew rapidly as predicted by O’Neill, stocks had mixed fortunes. The MSCI BRIC index now trails the S&P 500 over this century, and even lags behind the total returns for individual indexes for the four countries.

“Do not confuse the BRIC concepts,” O’Neill said in an interview. “My whole purpose of creating the acronym has nothing to do with investment.”

Russia’s war has, of course, wider consequences. The ongoing devastation on the ground in Ukraine has triggered market volatility globally. Commodity prices have surged in response to sanctions imposed by Western countries to isolate the country. That has sparked inflationary fears for big commodity and energy consumers and importers such as India and China.

The market turmoil has even hurt hedge funds that are designed to prosper in both rising and falling markets, with money managers such as Autonomy Capital Research, H2O Asset Management and EDL Global Opportunities facing double-digit slumps. Many have been forced to mark Russian bets to zero.

The BRIC Promise

O’Neill’s paper, “Building Better Global Economic BRICs,” was published on Nov. 30, 2001 and focused on how the global economy would be driven by the growth of emerging markets in the following decades. He argued that policymaking forums such as the Group of Seven should be re-organized to incorporate BRIC representatives.

Fund managers took notice. Two of the largest surviving funds, Schroder International Selection Fund – BRIC and Templeton BRIC Fund, started in 2005, while Goldman Sachs launched its own fund the next year. The Schroder fund grew to more than $4 billion, while Templeton’s money pool amassed $3.3 billion by 2010.

But the second decade of the century started to take shine off, and now they’ve reached a calamity. The Schroder fund, which was managing $710 million at the end of February, has declined almost 16% this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Templeton’s $450 million fund has slipped more than 14% after it marked Russian American depository receipts to zero when Russia’s markets closed, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

Goldman Sachs, meanwhile, closed its money-losing BRIC fund in 2015 and merged it with a broader emerging-market fund, joining a string of others to take similar decisions. Bloomberg tracks only 74 surviving BRIC funds now. The same number have shuttered over the years, while dozens have been acquired or delisted, Bloomberg data shows.

BRIC funds’ long-term performance pales in comparison to U.S. stocks, which were powered by quantitative easing and the surge in technology stocks over the past decade or so.

But to Chetan Sehgal, portfolio manager of Templeton BRIC Fund, the grouping still offers long-term value even without Russia. Resource- and energy-rich Brazil could benefit from an ex-Russia world, he said. “Though China has slowed down, its path will very much depend on how it navigates the external environment as many of the internal reforms have already been enacted,” he added.

To others, though, the concept has lost its charm. Ed Park, the chief investment officer at U.K. wealth manager Brooks Macdonald, said Russia is uninvestable, Brazil has lots of political risk and his firm can get exposure to China outside BRIC funds. “I don’t see us investing in BRIC as a concept in the medium term,” he said. “The economic drivers of the constituents are not as correlated as when the term was coined and some of the countries we would choose to actively avoid.”

As for O’Neill, he stands by the idea that these economies are growing in size and influence. “Despite the problems that Brazil and Russia have, because of the enormous success of China, if you look at where they all are together, it is still feasible that by the mid 2030s, the BRICs could be bigger than the G6,” he said.

Still, he said he’s never invested in a BRIC fund, and never will.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.