(Bloomberg) — The wild ride that bond traders have been on is far from over as market expectations for the longer-term path of Federal Reserve monetary policy appear at odds with the central bank’s own view.

Short-dated Treasury yields have alternately plunged and surged in the past few weeks as investors have tried to determine just how much the Fed will ultimately lift its benchmark and whether it might be forced to follow its tightening with a pullback if the economy starts to crater.

That’s helped, ultimately, to bring short-end rates higher and put market pricing for where policy is likely to be this year close to where Fed officials themselves see it. Looking further out into 2023, though, differences remain. And that potentially sets the market and the Fed up for a tumultuous reckoning, with inflation readings and Treasury auctions in the coming week among the key near-term flashpoints.

“The markets think the Fed being aggressive this year means inflation will come down enough to allow the Fed to shift,” said Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist at Charles Schwab & Co. “The Fed is pushing against this idea because when they are still tightening, they don’t want to talk about easing. They’ve got a big communication problem on hand.”

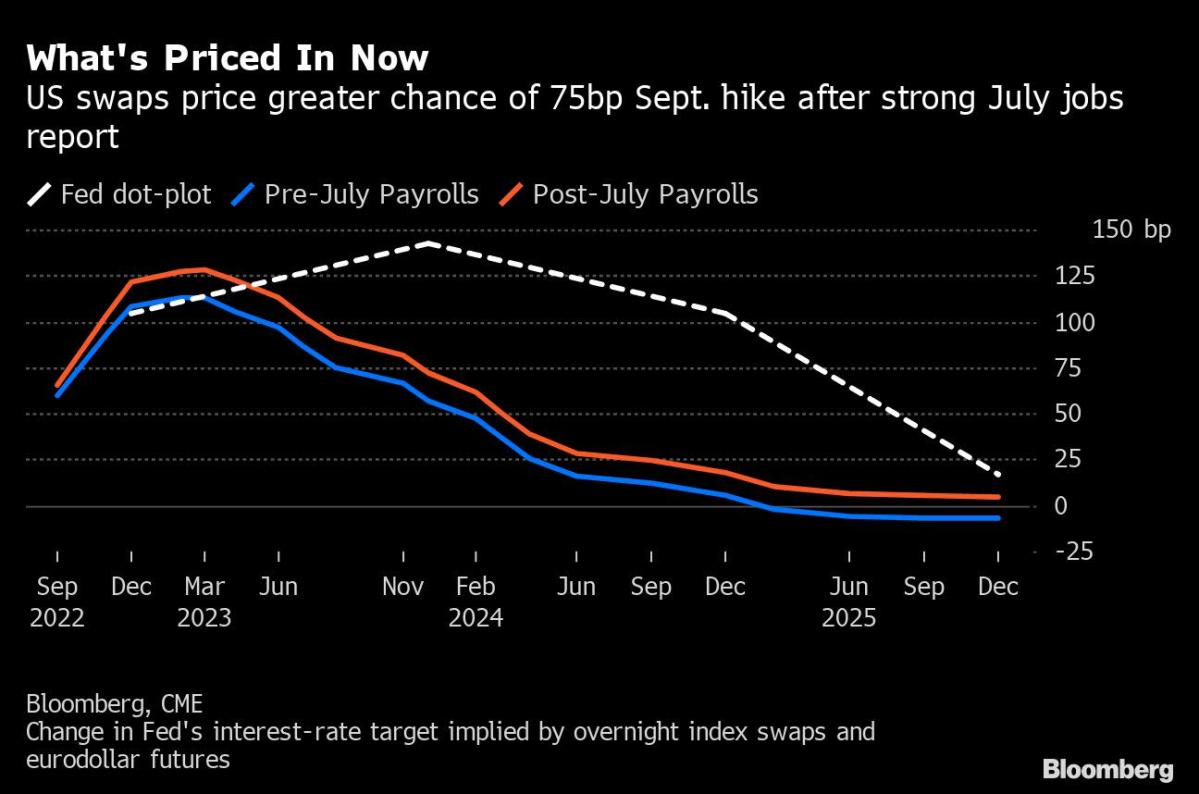

Whose view prevails remains to be seen, of course, but the divergences do underscore the Fed’s increasingly difficult communication challenge as it balances heightened risks around inflation, growth and financial conditions. This week witnessed a procession of central bank officials seemingly bent on driving home a more hawkish message. Combined with much stronger-than-anticipated economic data — in particular the blockbuster monthly jobs report Friday — that’s helped cement market expectations for bigger hikes in the near term.

But that was only after markets took a sharp detour in the other direction following a dovish interpretation of Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s post-decision press conference the week before. The Fed lifted its benchmark that day by a punchy 75 basis points, but the main takeaway of markets — though not necessarily all observers — appeared to be that an avowedly data-dependent central bank would be willing to halt its hiking campaign if and when growth crumpled. It was only after a swath of subsequent comments by officials that the market shifted in a more hawkish direction.

It’s not the first time the Fed has found itself with a communications conundrum of late. Heading into the blackout period before the June meeting, a time when officials don’t speak, it looked like the Fed was on course for an increase of 50 basis points. But by the time the meeting itself rolled around the market — encouraged by media reports — was primed for a move of 75 basis points, which was what eventually came to pass. That meant big shifts in the rates market, albeit in the days leading up to the decision itself as opposed to its aftermath.

Of course, it’s always difficult to predict how markets might react to particular Fed comments. Some observers of Powell’s July press conference homed in on his emphasis of the so-called dot plot — the summary of where policy makers predict the central bank benchmark is likely to be over the next couple of years.

Taken at face value, that might suggest that the market was at that time underpricing the amount of hiking likely to come, and that seems to be the message subsequent Fed speakers have been hammering home. But at the time, traders were more keyed on what they perceived as dovish elements, including Powell’s apparent abandonment of forward guidance and an emphasis on the importance of each coming economic data point in helping to guide the path for rates.

“It’s not that the Fed pivoted per se,” said James Athey, investment director at Abrdn Plc. “Rather, they opened the door to a pivot and indeed brought broader economic data back into the fold. Thus, it’s rational for investors with a very negative growth outlook and an expectation of falling inflation through year-end to start positioning for the inevitable pivot.”

One upshot of all this is that it risks unleashing looser financial conditions more broadly, which in Athey’s view is “the exact opposite of what’s needed right now.” That in turn could ultimately bolster just how much tightening the Fed needs to do, creating further potential disparities between the market and the eventual policy path.

The biggest divergence between the market and what officials have indicated is likely is concentrated in the outlook for 2023 rather than 2022. While trader expectations for exactly how much they’ll do September have wobbled back and forth — 75 basis points is currently seen as more likely than 50 — and there are variations in the months after that, the broad picture for where markets see fed funds at the end of this year isn’t a million miles from the Fed itself. The median prediction of officials for the end of 2022 is 3.375%, while the level implied by December swaps contracts is presently around 3.56%.

Beyond that horizon is where things differ and to some extent that speaks to different views of the Fed’s reaction function. The market, primed by years of near-zero rates and a central bank that’s shown its willingness to step in and cushion downturns, seems convinced that a slowdown in growth will bring down inflation, allowing the Fed to cut — perhaps not all the way back down, but at least to a more neutral rate.

Fed officials, meanwhile — potentially cognizant that inflation means this time might be different — are for now beating the drum about how resolute they plan to be in the face of inflation pressures. When asked about market pricing of Fed rate cuts next year, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard told CNBC Wednesday that he’s “not quite sure exactly what they have in mind,” and inflation won’t cool as rapidly as what the market expects.

How the divergence ultimately resolved is unclear. But for the moment it’s likely to leave bond markets volatile and subject to rapid about-turns on the back of incoming data and slight variations in Fed commentary.

“It has simply been a challenge for the Fed to communicate its hawkish intentions when market participants have been looking for a dovish pivot,” Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors wrote in a note to clients. “At some point, the Fed and markets will be realigned, and the data will decide whether the Fed needs to move to the markets or vice-versa. The Fed thinks the market will be the one that needs to move.”

What to Watch

- Economic data calendar

- Aug. 9: NFIB small business optimism gauge; non-farm productivity and unit labor costs

- Aug. 10: MBA mortgage applications; consumer price index; wholesale inventories and trade sales; monthly budget statement

- Aug. 11: Producer price index; weekly jobless claims

- Aug. 12: Import and export prices; University of Michigan sentiment gauges

- Federal Reserve calendar

- Aug. 7: San Francisco Fed’s Mary Daly on CBS’s Face the Nation

- Aug. 10: Chicago Fed’s Charles Evans at event in Iowa; Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari

- Aug. 11: Daly on Bloomberg Television

- Auction calendar:

- Aug. 8: 13-week and 26-week bills

- Aug. 9: 52-week bills, 3-year notes

- Aug. 10: 10-year notes

- Aug. 11: 4-week and 8-week bills, 30-year bonds

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.