(Bloomberg) — In a dusty corner of Oklahoma, close to where Erle Halliburton founded his eponymous oil services empire 103 years ago, a group of workers shows why US oil production growth has been underwhelming in spite of a price boom.

This particular Halliburton Co. crew is busy cannibalizing older frack pumps — the powerful, truck-mounted engines that help to squeeze hydrocarbons out of shale rock — to meet the high demand for gear in US oilfields. It’s hectic work, and currently extremely profitable.

Halliburton and its competitors are choosing this path — the reconditioning of existing equipment — over significant new investment in manufacturing for a reason. The oil services sector, much like the exploration and production companies it serves, is scarred by the severity of the previous industry downturn that’s only just receding in the rear-view mirror, and it’s keen to avoid a repeat of the experience, which included painful layoffs and downsizing.

Such caution means that, even with oil prices hovering close to $100 a barrel, there’s simply not enough hardware to satisfy demand in the US shale patch right now. The shortage of frack pumps, combined with a dearth of crews to operate them and sky-high prices for steel pipes, is calling into question US explorers’ ability to meet production forecasts this year.

“We’re kind of in unprecedented territory here,” said Rob Mathey, a senior analyst at industry consultant Rystad Energy AS. The fracking strain “is going to really lead to issues with E&Ps trying to grow.”

Any degradation of the ability of US drillers to deliver more supplies may serve to worsen an energy crisis that has stressed consumers globally, endangered economic growth and forced some governments to consider rationing for the first time since World War II.

US crude oil output tumbled in the early months of the pandemic and hasn’t yet returned to pre-Covid levels despite a rebound in global demand and the price spike that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Domestic production is expected to increase by 900,000 barrels a day this year, or about 7%, according to the average of several analysts surveyed by Bloomberg.

While that’s significant additional supply, it’s a far cry from earlier in the decade when US drillers routinely boosted annual production by double digits. Permian Resources, the shale driller formed by the recent merger between Colgate Energy and Centennial Resource Development Inc., plans to grow production by 10% next year, but will manage do so without adding drill rigs or completion crews in a “challenging operational environment,” said Co-Chief Executive Officer Will Hickey.

Extracting shale oil and gas can be divided into two distinct phases: the drilling, and then the fracking of the well. It’s the second so-called completion stage, in which a murky mix of chemicals and water is injected at high pressure to dislodge the buried hydrocarbons, that’s proving to be a pinch point.

Even before Covid, US shale was seeing a shakeout after years of break-neck growth had added to an oil glut. Frack fleets were scrapped en masse. Demand is now back — with a vengeance. A decade ago, a well was fracked with about 12 pumps on site, versus 20 today, said Andy Hendricks, chief executive officer of fracker Patterson-UTI Energy Inc.

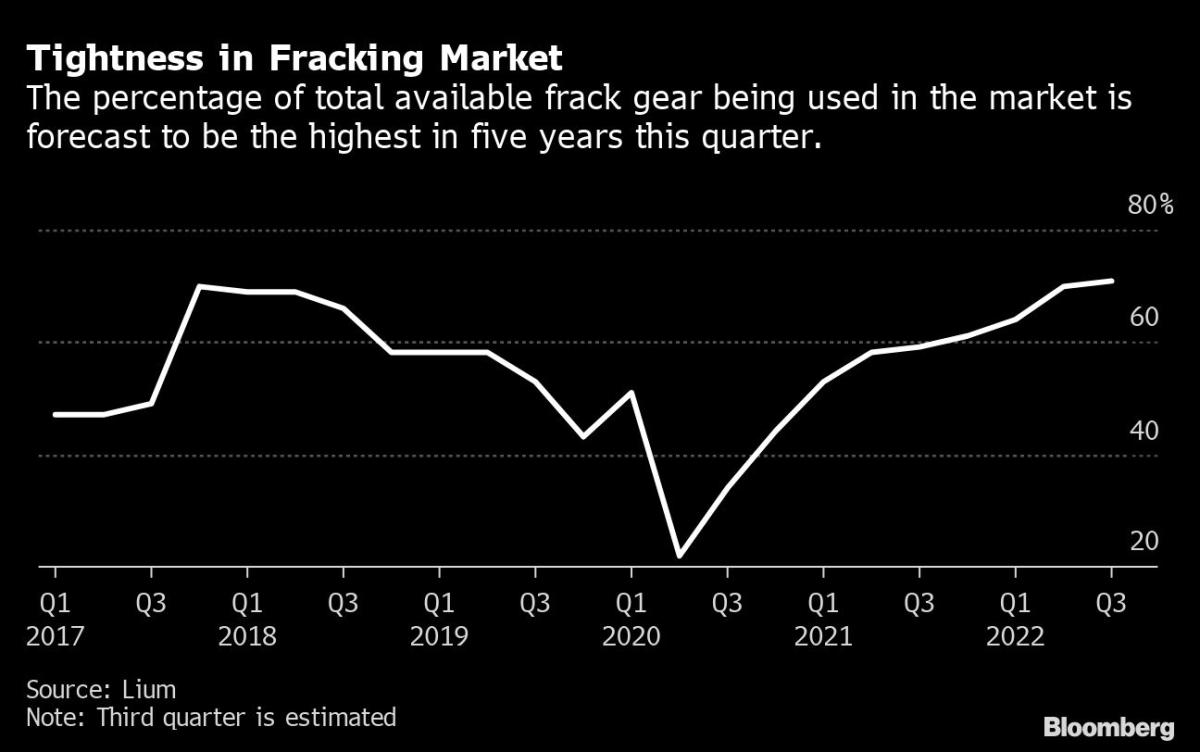

As well as the shortage of equipment, the estimated total of 264 fracking crews operating right now in US oilfields is 42% below what was seen in 2018, says industry research firm Lium. Overall, fracking costs are set to jump 27% this year, according to Kimberlite International Oilfield Research.

“We’ve had four different frack companies cancel on us because they don’t have the proper equipment or pumps with enough horsepower,” said Angela Staples, a senior vice president at Warburg Pincus-backed explorer Tall City Exploration LLC. “It’s difficult to put so much money into the ground and then be forced to wait,” she added, though Tall City still aims to meet its production growth target for the year, despite the delays.

For the oil services companies, higher prices have brought relief after the bleak times that followed the initial impact of Covid. Halliburton reported in July that North American revenues were up 26% in the second quarter, largely due to fracking. It warned that oil companies that don’t already have fracking equipment leased for new wellls will probably be out of luck for the remainder of 2022.

In a reflection of the sea change under way for frackers, Halliburton is now spending 80% of its manufacturing effort on refurbishments and just 20% on brand new fabrication. That’s a complete reversal from just a few years ago, according to Mike Gray, director of manufacturing at the Duncan site, who’s been with Halliburton for almost half a century.

“The dynamics with the maintenance side of it is so different,” said Gray, as a handful of workers nearby tinkered with repairs to a dirty pump. “We’ve got a lot of equipment out back that we can pull from.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.