(Bloomberg) — When the oil market liberalized in the 1970s, a group of commodity trading buccaneers led by the infamous Marc Rich made fortunes by connecting buyers and sellers and surfing the price swings of this newly tradable commodity. Half a century later, some of Rich’s spiritual descendants are hoping to pull off a similar trick in lithium.

A vital component in most electric-vehicle batteries, lithium is becoming one of the world’s most important commodities. Prices have soared to unprecedented levels as demand forecasts keep growing, leaving automakers scrambling to secure future supplies.

Yet until fairly recently, it’s been almost impossible to trade. Prices would be fixed in long-term private contracts between the handful of dominant suppliers and their customers, with no need for middlemen. Now, the surging demand is shaking up the way that lithium is bought and sold: Many supply deals have become dramatically shorter — with floating prices linked to the spot market — while exchanges from Chicago to Singapore are experimenting with new futures contracts.

And it’s getting the traders’ attention. Companies like Trafigura Group and Glencore Plc that make money moving commodities from copper to crude and coal around the world, are starting to wade into the lithium market. Traders say they can help the market broaden and mature, and reduce risks for other players in the supply chain. Some, like Trafigura and Carlyle-backed Traxys SA, are also investing in new production sources.

“The activity of traders in the lithium market should make this a more transparent and efficient market over time,” said Martim Facada, a lithium trader at Traxys. “It’s like oil in the 70s when governments would sell to consumers but then traders started providing services and that helped growing and developing the market faster. Lithium’s starting to go through that process.”

Of course, the comparison with oil 50 years ago isn’t a perfect one. The lithium market is tiny compared with more established and liquid commodity markets — annual world oil production is worth more than $3 trillion at current prices, versus $30 billion for lithium. The metal is also refined into highly specialized chemicals that some experts argue are much less fungible.

One of the concerns in the lithium market is that the extreme supply shortages create a risk that prices rise so high, or metal becomes so difficult to access, that automakers have to stop buying.

Commodity traders have a long history of squeezes and shocks in commodity markets, and the high stakes in lithium — so crucial to the success of the world’s decarbonization efforts — could leave them open to criticism. But despite the industry’s swashbuckling reputation, the traders insist they are treading carefully and are focused on helping to alleviate shortages, not make them worse.

“If a trader is to get involved, it needs to be done with an entirely different approach,” said Socrates Economou, Trafigura’s head of nickel and cobalt trading, who also oversees lithium. “You already have a price that can lead to demand destruction — if you’re going to have market participants driving the price higher, I don’t see how this market can sustain itself.”

Trafigura estimates demand will hit 800,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent this year — overshooting supply by 140,000 tons — and sees demand rising by a further 200,000 to 250,000 tons annually through 2025.

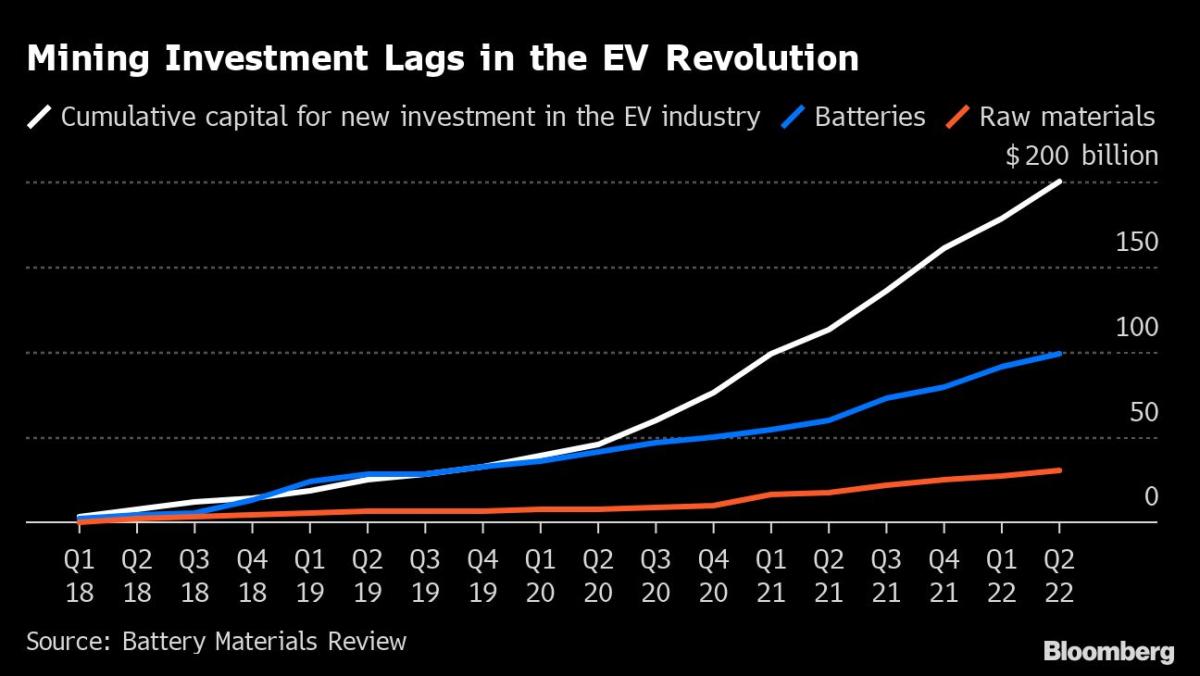

And while the world needs more and more lithium, investment in new supply has not kept pace with rising demand. Trafigura’s focus so far has been on tying up deals with early stage mining and refining projects. Traxys, another early mover into the industry, is taking a similar approach, scouring the globe for new sources of supply and helping to nudge them into production. The aim is to make money increasing the overall flow to car-makers, said Facada.

Other traders are also looking at lithium. Glencore, which is the largest producer of another key battery metal, cobalt, has invested in recycling startup Li-Cycle Holdings Corp. and is thinking about starting to trade lithium produced by the company, as well as third-party material.

Traders IXM, Transamine SA and Mercuria Energy Group Ltd. have all set up lithium trading books in recent years, while Japan’s Mitsui & Co. has long been active in the sector.

The traders are stepping into the lithium market at a time of dramatic transformation. For years, the main customers for lithium producers were largely niche manufacturers in sectors like pharmaceuticals and industrial lubricants. Now, as carmakers have taken over as the biggest buyers, miners have been shifting towards a shorter-term pricing model that better reflects the mismatch between demand and supply. It’s a trend that’s drawn comparison to a seismic overhaul in the iron ore market as producers shifted to spot pricing in the 2000s, but it’s placing a strain on consumers and producers alike.

Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk has said that spot prices have become “crazy expensive,” and after years of urging producers to supply more, he’s stepping up efforts to refine it himself. Meanwhile, investors are pressuring top miners like Albemarle Corp. to shift their contracts over spot pricing more aggressively, potentially adding to the strain on their customers as the buying frenzy continues.

It will probably take some time before lithium matures to become more of a tradable commodity market, said Kent Masters, chief executive of Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium producer. With the spot market growing, the next key milestone for the industry will be the development of liquid futures contracts.

“We do think ultimately there’ll be an instrument out there where you can hedge lithium prices or speculate on the market financially,” he said in an interview. “It’s a good thing once it matures. But it’s going to take some time — it’s not today.”

In addition to helping make markets more efficient, traders say they can also manage risks for automakers and battery producers that are starting to look at mining projects and investments in a way that would have been unthinkable for many just a few years ago, as supply fears begin to rise. That will take them into riskier jurisdictions than they’re used to operating in, and leave them exposed to cost blowouts and wild price swings that are common to the mining industry.

“One of the roles we play is to connect different levels of supply chain to provide some level of price protection,” said Claire Blanchelande, Trafigura’s head lithium trader. “In addition to banks getting involved, car-makers are also getting comfortable because of our involvement.”

–With assistance from Jack Farchy and Thomas Biesheuvel.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.